The art of religion news in the broadband, multimedia, & social age, 2000-2005

If the web in the 1990s was like millions of springs connected by creeks, the 21st Century brought the rise of gushers of digital creations connected by fast. big rivers of data made possible by broadband networks, faster computers and more storage space.

In 2000 ExciteAtHome introduced a now widely used design structure for broadband networks. The increase of bandwidth meant that interactive and multimedia websites could run smoothly. In theory it became possible to develop deeper immersive multi-media experiences of news reports. News media organizations, however, still saw digital technology as a new tool, not as a transformational engine. The news rooms were becoming quieter with the displacement of typewriters, but essentially they were vast rooms that still resembled factory floors. As old media leader New York Times held a competition to build its $850 million headquarters, Google opened up its New York City “office” in a Starbucks on 86th Street in Manhattan.

Brooklyn-born Jeff Sharlett teamed up with Peter Manseau to promote through KillingTheBuddha.com a fresh, attention-getting, sometimes snarky type of religion reporting. Its style was in tune with the new tech generations.

In 2001 crowd-sourced media received a boost with the formation of Wikipedia. Although this development challenged encyclopedic efforts like Beliefnet, it did not compete in breaking news. Beliefnet sought to replace the lost revenue by partnering with ABC News to co-produce religion news stories, though that coincided with the layoff of Peggy Wehmeyer as ABC’s religion reporter. Financially wobbly, Beliefnet still proved that online religion news reporting could compete with any news media.

In 2002 Beliefnet.com won a Webby Award for the category of religion and spirituality. After declaring bankruptcy, Steve Waldman was named CEO tasked with rebuilding Beliefnet. In 2003 it won the Online News Association’s award for general excellence in online journalism in the independent category for sites with more than 200,000 unique visitors a month. Beliefnet had over one million unique viewers per month. The website shifted its focus away from news and information toward nurturing spirituality.

Snarky reporting gained another important promoter with the founding of the gossipy Gawker.com. The company launched or acquired multiple websites, including Gizmodo in 2002. Gawker’s snarky coverage of news media resonated with a lot of journalists who liked the idea of news reporting with an attitude. Although generally successful, a number of the sites failed to generate much interest.

A media organization could lose or gain audiences quite quickly! What the online gods gave, they could also take away. Now, everyone had the power of creation, particularly after the introduction of TypePad, WordPress, Blooger by Google and MySpace in 2003. Additionally, consumers had exponentially more platforms (websites, print media, cable, radio, over-the-air television broadcasting, and movie theaters), so they started to think in terms of quick switches between the platforms. Indeed, a former consumer of news reports could also start producing or aggregating their own news media, moving audiences to a new platform or niche within a platform. For old media it was like a shift of the gods from a limited number of oracular networks to a new god under every website.

Henry Jenkins reported on this atmosphere at one media gathering, the New Orleans Media Experience that took place in October 2003:

Inside the auditorium, massive posters featuring images of eyes, ears, mouths, and hands urged attendees to ‘worship at the Altar of Convergence,’ but it was far from clear what kind of deity they were genuflecting before. Was it a New Testament God who promised them salvation? An Old Testament God threatening destruction unless they followed His rules? A multifaced deity that spoke like an oracle and demanded blood sacrifices? Perhaps, in keeping with the location, convergence was a voodoo goddess who would give them the power to inflict pain on their competitors? … the record industry types were sweating bullets… (Convergence Culture. Where old and new media collide, 2006, pages 6-9)

A new way of being religious was to attend a congregation that had an open wall to the digital world. It was not having “multi-media” or being “high tech” or a dollop of “the kid’s culture. It was digital as a daily habit of operation. The old complaint “Daddy, I already know that” was not a signal of generational rejection but an announcement of a reformatting of parental values into a new cultural medium. For example, New Song Church in Los Angeles gave every member a twitter account to receive church updates, and posted members’ photos, videos, and comments. A photo booth was opened on Sundays for “selfies.” David Mahones and Brent Gudget made entertaining and moving short documentaries about homelessness for their Chronicles/Deidox project, which was distributed through Youtube, churches and Bible studies.

With the encouragement of online news guru Jay Rosen, Jeff Sharlet and Kathryn Joyce launched TheRevealer.org, “a review of religion in the news and the news about religion.” Disdaining the characterization of their religion reporting as “snarky,” the website wore its opinionated style as “polypartisan.” The end results were creative and fresh religion reports with sharp elbows.

In 2003 the virtual reality world Second Life was born. Soon, there were many virtual religious congregations. Real life pastors, like Rev. Christopher Benek of the First Presbyterian Church of Ft. Lauderdale, proposed that virtual congregations could serve the homebound, the sick, and the poor while also providing for world-wide gatherings through Second Life.

Even a simulation of a daily paper like the New York Times was produced for the Second Life inhabitants. Among the news media in Second Life were Second Life Newspaper, New World Notes, and The Alphaville Herald. CNN, Reuters and other news organizations experimented with producing for Second Life or using Second Life as a way of finding out news about real life.

Most of the virtual churches were short-lived, and Second Life’s pornographic section flourished. In his Virtually Sacred scholar Robert Geraci chronicled some of the troubled efforts of to set up virtual reality congregations. One of the main problems was that LifeChurch.tv tried to simply reproduce the non-virtual church without taking into account how the virtual world allowed many different new styles of interacting. So, their congregations seemed alien to the virtual reality, a little too prosaic.

Because of the ephemeral nature of the internet, some of the old media were stuck in the denial stage about the revolutionary changes underway. But there were warning signs all over the internet where users were becoming accustomed to giving instant feedback to media organizations that weren’t used to such exposure. By 2003 old media was experiencing massive disconnect with its audiences, particularly its conservative and moderate segments. After the New York Times found out in 2003 that one of its reporters had been falsifying news reports with weak editorial oversight, the discovery was blasted all through the web with a “we-told-you-so” jibe attached. A mere “we regret the error” printed in an unread portion of the paper, a day or two after the story, came long after the critics already were dominating the narrative.

Disorientated, the Times took the opportunity to start rebooting itself for the Twenty-First Century. In a letter published in 2005 as a response to an internal self-study, “Preserving Our Readers’ Trust,” the executive editor Bill Keller announced that the paper had discovered a wide-ranging disconnect with its conservative religious audiences. It was a tour d’force of taking a crisis as an opportunity to adjust to the new world in which ignored religious voices could easily establish competitive platforms. For example, in 2004 Lila Rose, a conservative pro-lifer, founded in her home the investigative media organization Live Action which specialized in posting Youtube undercover video exposes of abortion providers. Further, social media like Facebook, which was founded in 2004, would quickly became forums of media comeuppance, often through the pasting of links to news features or commentaries like Live Action’s videos that were more favorable to moderate and conservative religious publics. Opinion surveys indicated that only a minority of Americans thought that the national news media were “objective.”

Online news reporting could also jujitsu the slower traditional print media by aggregating their stories online before a paper could be delivered to the front porch. In 2005 Ariana Huffington with the help of Jonah Peretti, Ken Lehrer and Andrew Breitbart kicked off the Huffington Post, which used traffic counting metrics to mix aggregated stories, some original reporting, and blog posts by unpaid famous and not-so-famous people. Later, it included a religion section.

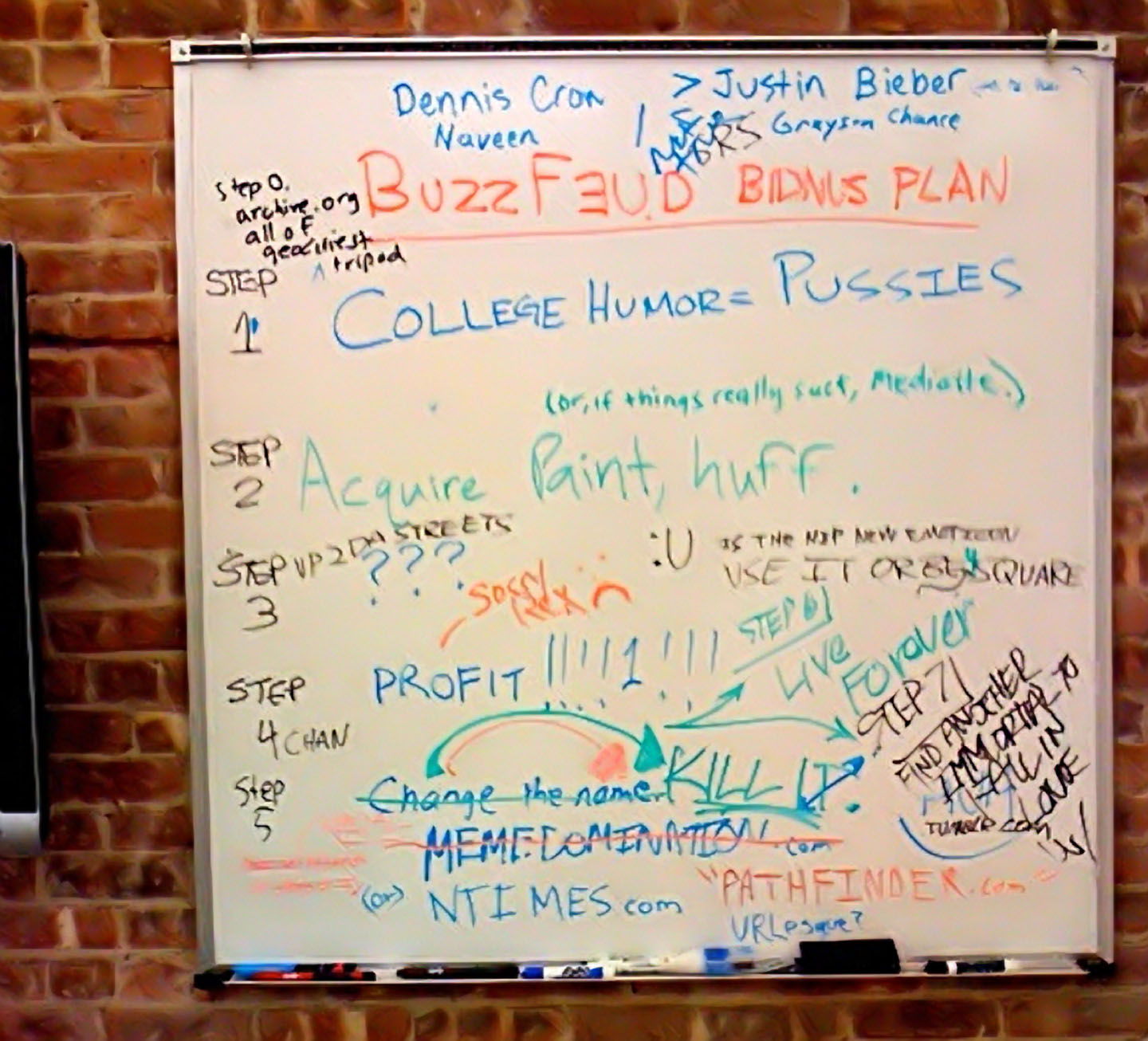

In the Summer 2006 HuffPo co-founder Jonah Peretti develops his viral ideas at a start-up called Contagious Media, which eventually leads to BuzzFeed.

In 2005 Youtube came online with the explosive opportunity that every news website could have plenty of video material for embedding into news stories. Co-founder Jawed Karim posted the first Youtube video, which was of him at the San Diego Zoo. His informal way of producing and posting video of his personal experience displayed the coming predominance of video qualities like hand-made, first hand personal experience, informality and quickness of posting. Regular media outlets resisted using Youtube because it seemed so out of line with current news media values and identity as “professionals.”

Google put also together several acquisitions to launch Google Maps. Who knew that mapping of the world would make Google the Columbus of the Twenty-first Century? In June 2005, the company released Google Earth with satellite views of most places on the globe. Armchair explorers could go see and explore most places in the world. Reporters did street reporting by looking at Google Street View.

In preparation for writing about the religious places of Iranians in New York City, an Iranian reporter in New York could take a look back at her old neighborhood in Isfahan, Iran, trace the footsteps of her uncle on his way to Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, and stop in at Roozegar Café to remember the time that her cousin treated to its notable coffee.

Leave a Reply