The art of religion news in the Browser Age 1990 – 1999

The 1990s decade opened with a controversy over the possibility that virtual reality might cause young people to lose their sense of actual reality. The New York Times opined, “…psychologists who now worry about children losing themselves in video game fantasy worlds would no doubt find artificial environments an even bigger problem.” The warning to “Stop” crossing over the frontiers of reality was a refrain that just got lost as “system noise” to a rapidly expanding digital revolution.

The high tech world was pushing across frontiers never before crossed. Silicon Valley was getting a center of the universe feel that New York had.

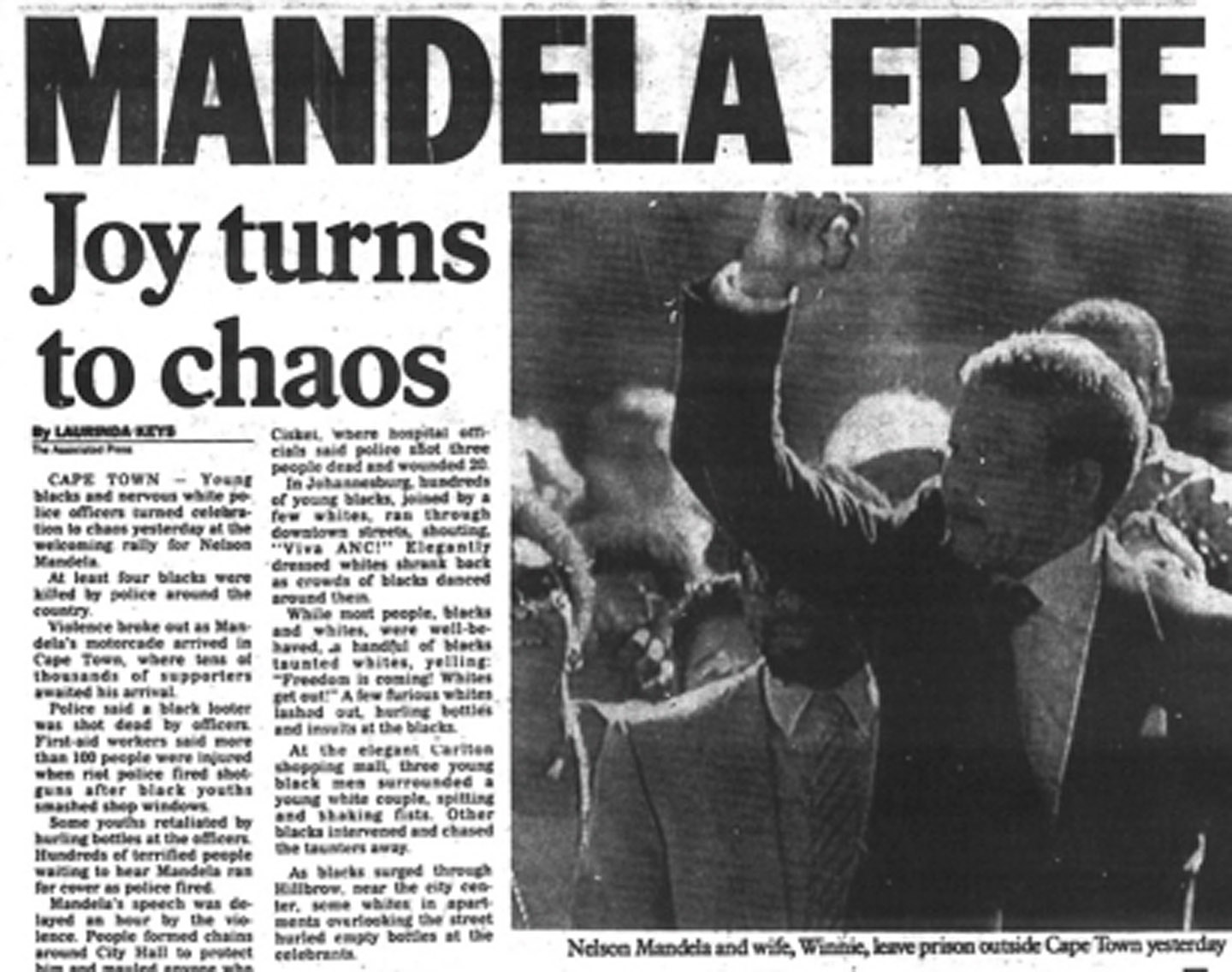

The networld started to empower more campaigns like “Free Mandela.” Source: NY Daily News, February 12, 1990.

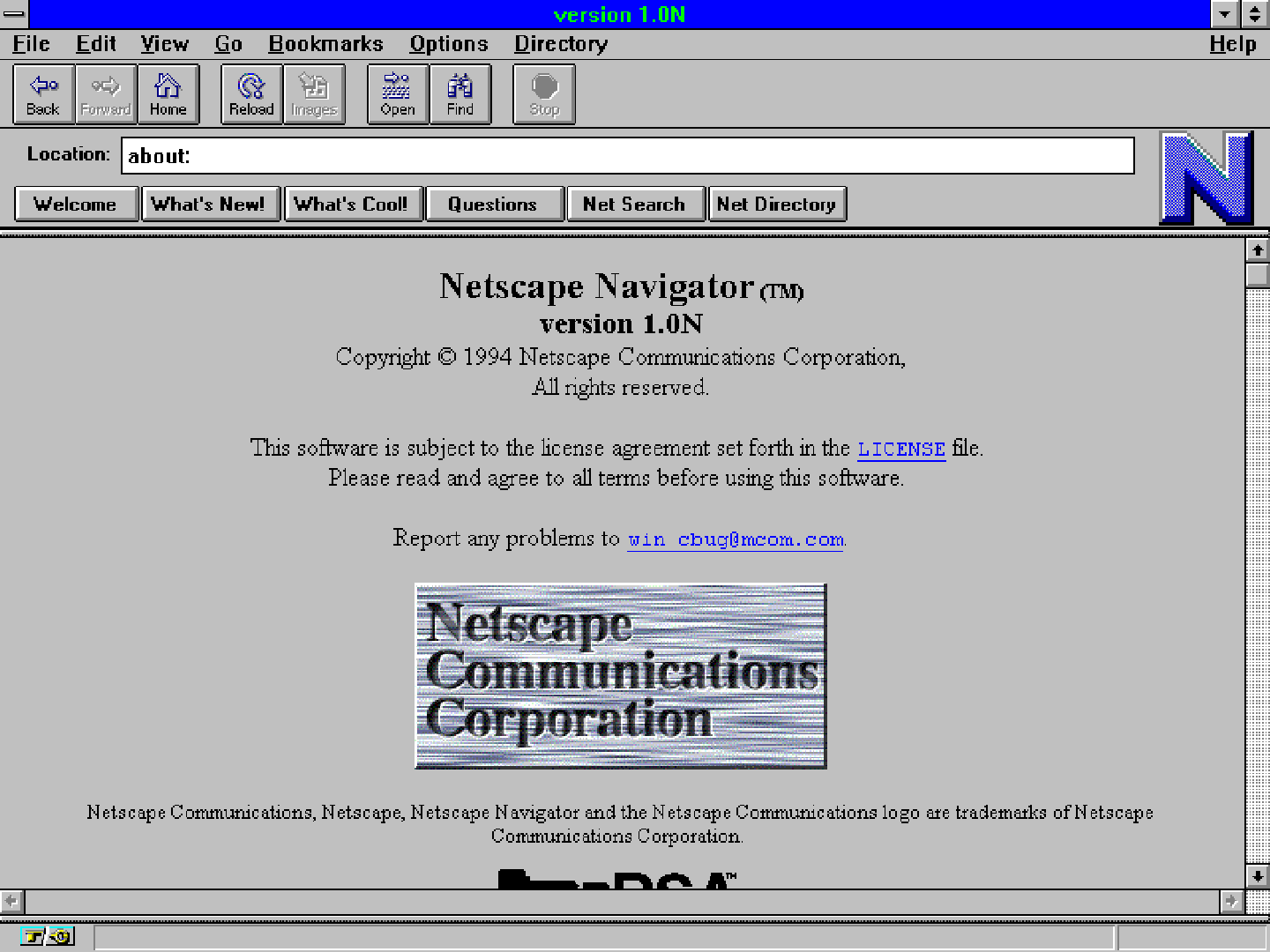

The biggest step forward was the invention of the browser which enabled the display of text, multimedia, archives and the embedding of interactive programs so as to create an immersive world in which one could live as a digital native. It was like being a magician who could invoke new sights at the click of a finger. In 1990 Nicholas Negroponte called this Being Digital. A new demographic was becoming orientated toward consuming news through digital delivery vehicles. The growth of this population really shot up with the introduction of the Mosaic browser in 1993 and other technologies.

Mosiac was the first text and visual browser. Because the University of Illinois appropriated the browser as its intellectual property, one of its main student developers, Marc Andreesen, told Silicon Valley developer Jim Clark that the commercialization of the new software would be bungled. He suggested that they develop “a Mosaic killer,” which they did in the form of Netscape. That development in turn provoked Microsoft to protect its competitive edge by launching Windows Explorer, a huge success.

During the same year, ATT introduced the first smartphone, Simon, and AOL introduced Instant Messaging. AOL’s Ted Leonsis sent to his wife the first AOL Instant Message that read, “Don’t be scared…it is me. Love you and miss you.” She replied, “Wow…this is so cool.”

In 1994 Yahoo introduced the concept of a hub portal in which multiple sources of information and features on the web were accessed through one portal. Audiences’ commitments to portals like Yahoo and AOL was like becoming a member of a popular club. However, it was getting easier to start your own club tailored to one’s interests. Blogging platforms that were becoming accessible to individuals furthered this trend. The introduction of the online banner ad by HotWired.com also meant that individuals and small start-ups might even be able to collect dues for their clubs. (HotWired.com’s ad promoted the old, old tech in the form of seven art museums and was sponsored by aging tech AT&T.)

First online banner ad was an unatttactive strip across the top of hotwired.com meant to be clicked.

Other digital initiatives undermined the giants and put more direct power into the hands of the individual. No longer did you have to depend on the local bookstore rep as the gatekeeper to what you might be able to read. I remember that my local bookstore didn’t admit African Americans. Amazon laid the bookstore to waste but sure did put more books into multi-colored hands. Maptitude released its relatively low cost, easy to use Maptitude 3.0 so that anyone could do high quality data journalism through mapping.

In 1996 MapQuest introduced to the internet the power of data-driven, interactive graphics through its mapping software. In the same year, Murdoch established Fox Cable News. Its graphically-intensified environment matched the tabloid newspaper’s brazenness.

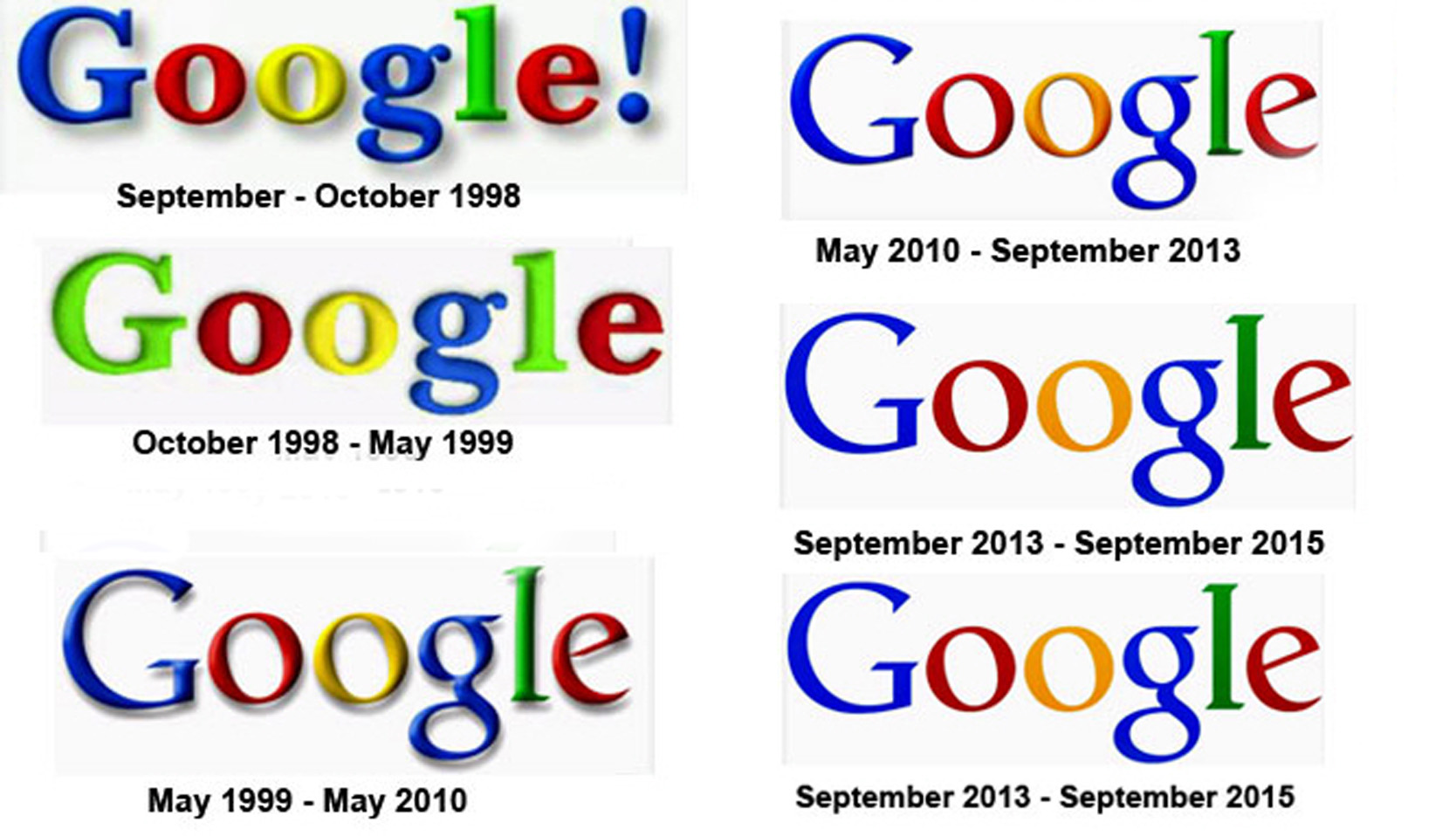

However, on the web, no matter how brazen, a news report had to be found first. Standard search engines worked by search terms, but the hits weren’t well organized by quality of the information or by relevance to the searcher. At Stanford two students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, were experimenting with evaluating information on a website by how many other websites linked to it. Also, the linking websites were rated on a scale of authority by how many links they had.

In 1997 Page and Brin registered Google.com as the address for their search engine which they had been developing. They announced that it would “organize a seemingly infinite amount of info on the web.” Google’s ability to find the highest quality of information with the most relevance to the searcher made it possible for small circulation websites to win audience if they met Google’s criteria.

In June 1999, MoveOn started raising money for political campaigns, raising what was at time an astounding $2 million for the 2000 election. According to Michael Cornfield, director of the Democracy On Line Project at George Washington University, MoveOn’s achievement created “a change in attitude” in the political fundraising community….It is like a bell has gone off. The race is on. ‘Let’s raise money online.'” Of course, online news media got the message also.

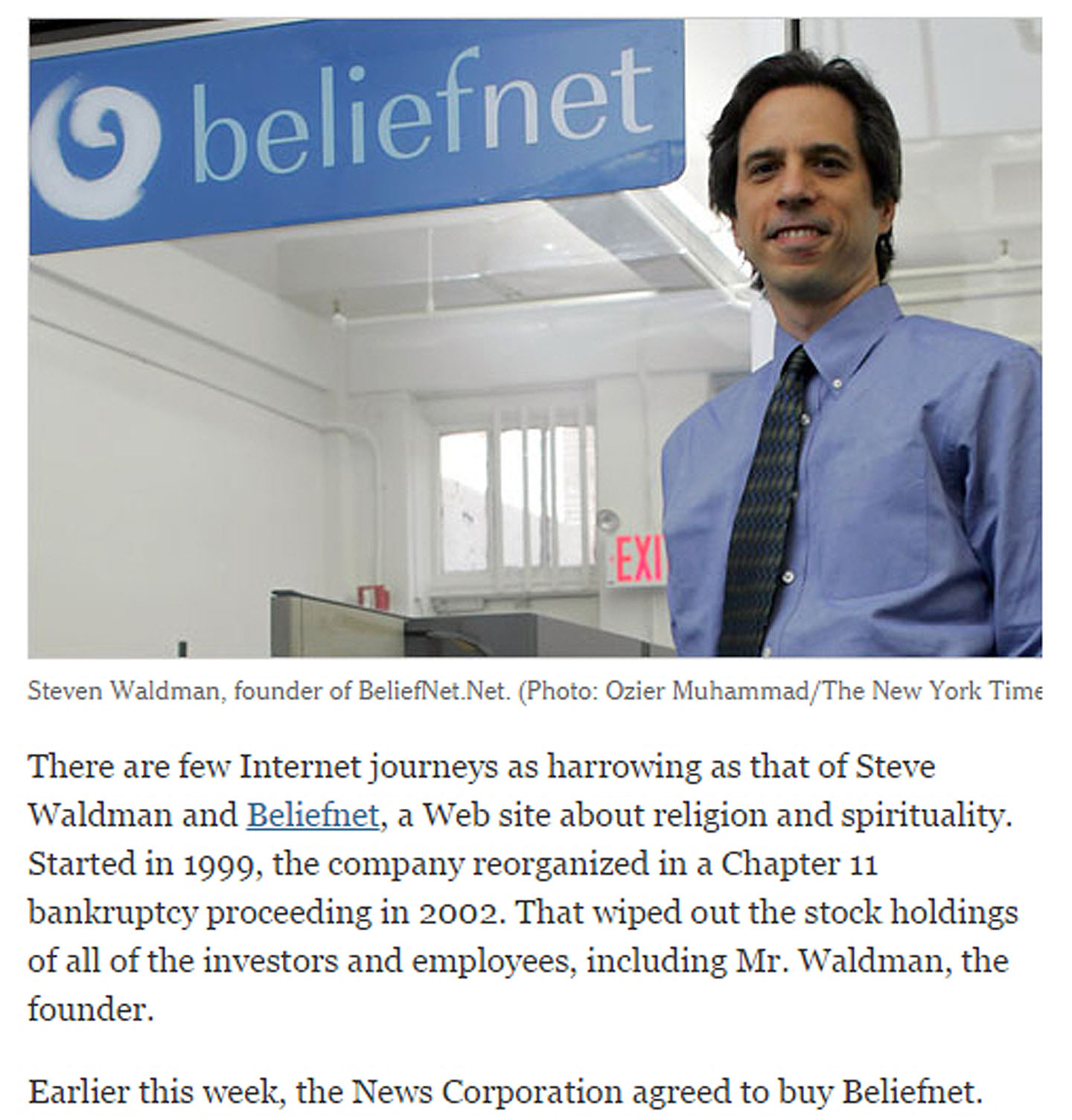

Just before the decade ended, in 1999, Steve Waldman, formerly of U.S. News & World Report, launched the first major online religion journalism site, Beliefnet. Its strengths were also weaknesses. It covered all religions without much distinction, losing audiences who were mostly interested in their own religion. It poured tremendous effort into hiring dozens of expert writers to create an encyclopedia of religion on the web. Many of the articles were excellent, but they came online just before Wikipedia launched its much cheaper crowd sourced encyclopedia. With many “firsts,” the site still crashed financially after the dotcom bust of 2000. Beliefnet was briefly revived before being sold.

The decade started with old media passing on warnings about the ill effects of the digital revolution. The grumpiness has continued up to today. The decade ended with a brilliant success at religion reporting that was tripped up by old media attitudes toward conservative religions and the emergence of social media as a huge engine for reporting. The religious experts place as gatekeepers at key places in the distribution of knowledge about religion were supplanted in many cases by the power of millions of lesser experts or hobbyists working together.

Michael Yang, founder of shopping site MySimon.com in 1998, was one of several Silicon Valley execs who wondered how the digital age would affect religion.

Leave a Reply