The City Q/A. Retrospectives/Retros II

A Journey through NYC religions has created a vertical (feature series) called Retrospectives to show how the great questions of life have always been central to New York City.

The city poem is:

Make a buck here, but better ask, why does it matter?

Look good on the runway, but better ask, do you have substance?

Be clever, but better ask, will your ideas last?

Do entertainments, but have you forgotten those who are in trouble and need?

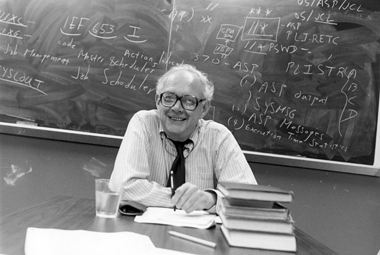

We are connected with our pasts by the Question/Answer process of religious life. What does it all mean? How can I live a better life? What is right and wrong? How much should I care about my neighbor? Does my secular or other religious neighbor provide anything of interest or value to the city? Religious Q/A is the way urban life is lived. The fragments of city life are aligned continually with narratives of greater purpose, morality and compassion. Whether the debates center around class, power or gender, religion has played an important role. Even in the rejection of religion, the narrative of city life is religiously determined. When the Jewish controversialist and editor of Dissent magazine,Irving Howe, gave a vigorous “No!” to Orthodox Judaism, the religious moment is the Big No to religion, Secularism.

You can tell how his secularism functioned like a scriptural God who reveals Himself and conceals His enemies under judgment. Howe shined a very bright light on the material factors of life as if it was a kind of materialist Glory. For Howe secularism and materialism was Truth. Simultaneously, he cast religion into a dark silent tomb, basically ignoring it as a causal force in history. His generation of intellectuals thought religion was on its way out—a has-been of history.

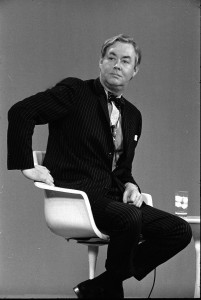

Even his opponents like the political scientist and U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and criminologist Nathan Glazer conceded that religion was on its way out and would no longer play an important role in New York City politics. Moynihan had a huge impact on NYC social policies through his authorship of the War on Poverty.

The most famous tract of the War on Poverty period may have been Michael Harrington’s 1962 book The Other America. President Kennedy read the book and ordered the staff to work on drawing up the War on Poverty. One staffer was Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who wrote a famous tract on the crisis of the African American family. One thing that stands out about Harrington’s work and, later Moynihan’s, is that they mostly ignored the role of faith, worldview, and values.

Later, Harrington admitted that he had left a hole in the heart of the poor. Toward the last years of his life he wrote The Politics at God’s Funeral. The Spiritual Crisis of Western Civilization (1983) and lectured on the need to add the spiritual dimension in addressing poverty and politics.

During his War on Poverty days, Moynihan himself only mentioned religion in passing. All of his implied solutions were secular government initiatives that might use the church but didn’t value faith-based solutions for their own potential. Many African American churches participated in the War on Poverty, but their most important assets of moral discipline and spiritual transformation did not have a legally-sanctioned role in the programs. In fact the officials promulgated a secular mindset.

The Moynihan report on the Black family itself hardly mentions the church, which is the primary social institution in the African American community. Partly, the omission was because in the 1950s federal government data collection ceased to include religion as one of its topics. Moynihan was asked to work with federal data sources. Also, Moynihan was beginning to despair over the possibility of religious influence in politics. In his Beyond the Melting Pot he concluded that religion would play no future role in politics in places like New York City, his home town. This is a conclusion that his co-author Nathan Glazer later regretted.

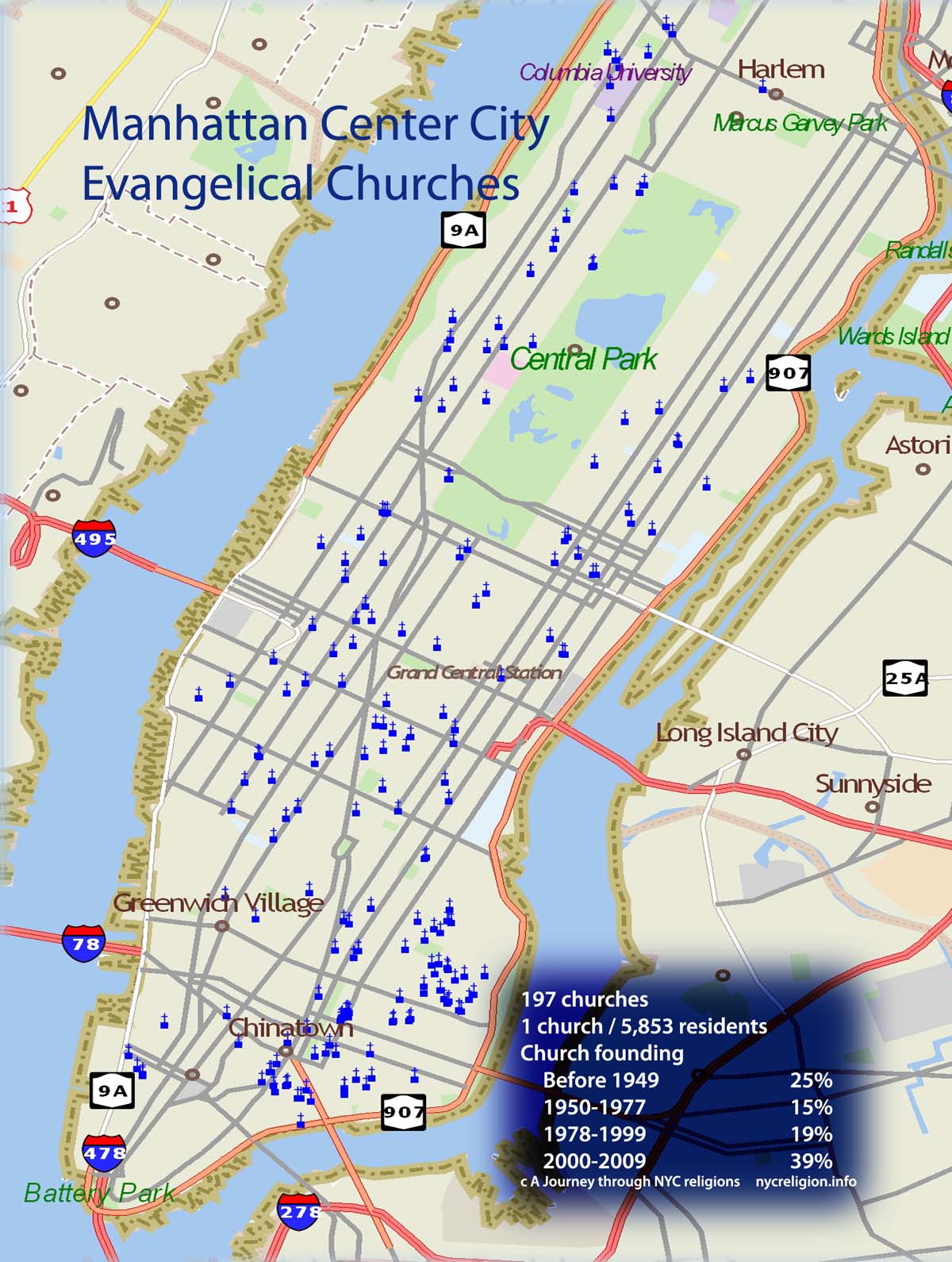

Such a secularist vision of New York City was appropriate to a mere episode in the life of the long history of the city. Even before these redoubtable thinkers passed away, religion was renewing its institutional presence in the city. Religion started to peep out into the Q/A conversations of our urban life. It first happened in the boroughs, particularly among those with life-challenging problems like drug-addiction and criminal enmeshment and among those who found that secular materialism was an inadequate account of life in the city.

Today, Secularism in the city is trending downward. It is being forced to justify itself in the face of resurgent religion. As the religious Q/A process reasserts itself, Secularism is recovering its own Q/A: can I live a satisfying and meaningful life without God?; what is secular morality?; if this material world is all there is, what is compassion?; and does my religious neighbor contribute anything of interest or value to the city?

The religious and the seculars also have plenty to say about each other’s shortcomings. Those disagreements should not muted, but they are not necessarily the only words that they can or should be saying to each other.

We are reverting back to traditional secular ideas that came out of religious traditions that wanted to prevent too much power being handed to the state by virtue of its policies claiming to be God-endorsed. Religiously-motivated democratic movements created the idea of that no one religion should dominate the public square. Somehow over time, the idea grew that Secularism had the right to dominate the public square. But secularism itself abused its power by attempting to force the religious voices out of the public square. That idea is under challenge because it resulted in so much conflict in our culture wars.

Instead, New York City seems to be settling for a postsecular public square. Mayor Bill De Blasio, who certainly has policies that are not popular with some of religious New Yorkers, has avoided strident culture wars by allowing religious people to have a voice on the public square, even if he doesn’t agree with them. When reporters at The Vatican recently asked the mayor if would consider becoming a Catholic, he replied in a nuanced way by appraising the high importance of Pope Francis’ leadership while adding, “It’s philosophically very important, but it’s not something where I’m going to become a practicing Catholic. It’s something that means a lot to me personally.” This attitude is a healthy reversion to an understanding of New York City as a place of Q/A about great existential questions by both secular and religious New Yorkers. Journey’s task is to provide Retrospectives so that we can re-imagine the city as the postsecular city in continuity with its past. We believe that the postsecular journalism project will be good for democracy here and in other places where the religious and the secular are facing off in intense conflict.

Leave a Reply